Escape Novelty Blindness

Some things seem obvious to me now, but they took years to learn.

9 Mar 2015

Two things that took me an embarrassingly long time to realise:

-

It wasn’t obvious to me that I even had anxiety, despite being constantly anxious forever.

-

Hiding it, repressing it, and pretending everything was okay just made it all worse.

These things seem obvious to me now, but these minuscule lessons took years to learn. How can that be possible?

One reason is that, put simply, anxiety is awful. It acts as its own defence: we’re so distracted by how unpleasant it feels that we can barely focus on doing anything about it. We just waste our energy wishing it was gone. This ‘failure’ makes us feel worse, and we become even less able to solve the problem, as we’ve now got even more to feel bad about.

But there’s a second problem: Novelty Blindness.

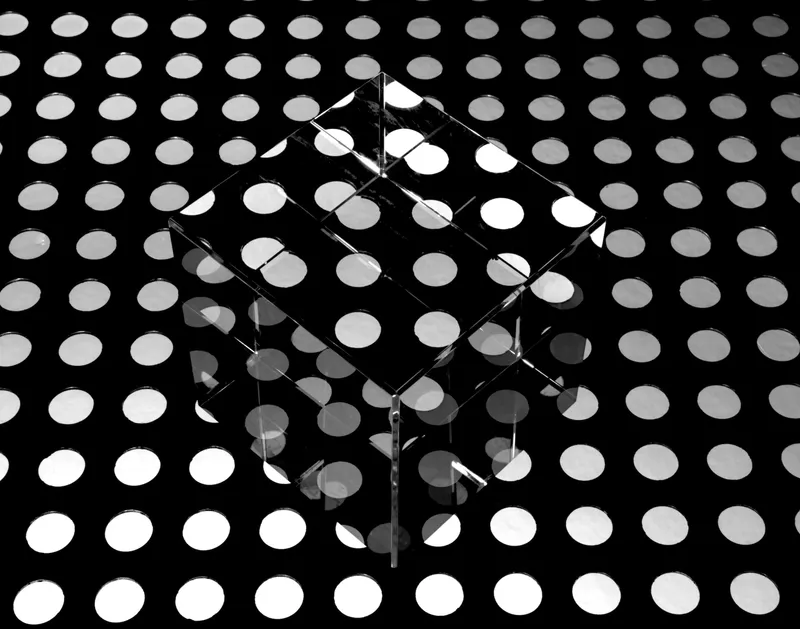

It’s likely that you’re reading this in a familiar place, or at least in a place where you’ve been before. I’d like you to pause for a moment, and consciously notice something - anything - which surprises you about this place.

Go on… Notice something new, or surprising, or that you had forgotten about wherever you are right now. I’ll play along…

I’ve sat at this desk for a large portion of the last several months as I’ve been finishing off this book. Here are three things I noticed in about five seconds of attempting to notice something new about this depressingly familiar spot:

-

A misshapen green money-box which was just above my monitor, right in front of my face.

It had £1.12 in it! Profit! -

A carved metal tankard with the word “WHOPPA” on it.

I’ve owned this for about fifteen years, but hadn’t noticed it sitting directly in my vision for the last six months. -

Some holy water in a plastic bottle shaped like the Virgin Mary, balanced on some Chinese worry balls. (Don’t ask.)

Three fairly surprising items had been in my field of vision for months, and yet I would NOT have been able to recall they were there if you’d asked me five minutes ago. I was completely blind to their existence.

Their descriptions make them sound as if they would stand out. But our brains are amazing at fading into the background anything that has become normal.

This is how anxiety becomes invisible to us. “What do you mean, I have anxiety? Doesn’t everyone spend 3am-4am every night worrying about diseases they probably don’t have?”

This is how solutions appear obvious in hindsight, but impossible at the time.

This is how I took years to accept the three fairly obvious truths I began this blogpost by recapping. My brain was so used to viewing everything in a certain way that I’d forgotten it was possible to take on a different view.

The good news is that this is not an inevitability. Once we’re aware of our innate tendency to get stuck in certain modes of thinking, we can get ourselves out. Becoming aware of the possibilities opens us up to new thinking.

If it’s possible for me to fail to notice weird items on my desk right in front of my face, then perhaps the way I currently think about myself isn’t the only possible way I could think. Perhaps the terrifying channels my thoughts go down when I consider my health aren’t the only available channels.

There are probably options in my thinking that I never considered, because I simply didn’t notice that they even existed.

We can use the brain’s tendency to form habits in our favour: by making it a habit to search for fresh perspectives and alternative ways of looking at things.

Not every new perspective is necessarily better, of course. But, if we’re constantly anxious, we already know that our current perspectives are failing us, so sticking with them is guaranteed to keep us where we are.

Conversely, if we try enough new perspectives, we will eventually find some that help us out. Embracing these will be the first concrete steps on the road to a less anxious life.

The first step, then, is to be aware that our thoughts and ideas are just a tiny subset of all the possible thoughts and ideas we could be having, and to be open to the idea of exploring alternative perspectives to see if any of them are helpful to us.

Important Note: It’s possible to misinterpret this idea as “My perspectives are wrong, so I’m to blame for my anxiety”. This is both unhelpful and untrue.

It’s also a whole other topic. Remember, anxiety is a tremendously complex knotted tangle: we pull on one strand only to find it’s attached to - and entwined with - several more.

Right now we’re pulling on “new thinking” and finding that it might be connected to “self-blame”, which is another strand entirely. We will talk about that strand later, but for now just take it on trust that self-blame is the wrong way to view the importance of new thinking. (If nothing else, habitual thinking is part of the design of the brain: we don’t need to blame ourselves for acting in a way that’s consistent with our actual biology!)

As a general rule, blaming ourselves (or anyone, for that matter) for our anxiety is unlikely to make anything better, so until we develop a solid coping strategy for unravelling that particular strand (which we will), for now let’s just not tug on it.

To summarise: We want to allow new solutions to our problems to come into view, which means we must begin thinking in new ways. We can do this anytime, anywhere, by making an effort to notice new things around us and searching for fresh perspectives.

If we try, we can bypass the brain’s automatic anti-novelty filters, and find new ways to look at everything. Even practising silly things (like noticing objects we normally filter out) helps to get into the habit of embracing change.

Neil Hughes is the author of Walking on Custard & the Meaning of Life, a comical and useful guide to life with anxiety, and The Shop Before Life, a tale about a magical shop which sells human personality traits.

Along with writing more books, he spends his time on standup comedy, speaking about mental health, computer programming, public speaking and everything from music to video games to languages. He struggles to answer the question "so, what do you do?" and is worried that the honest answer is probably "procrastinate."

He would like it if you said hello.